The following notes come from my recent research into one of my five x great grandfathers John De Morgan who arrived in India in 1711 as a private and eventually rose to become the commander in 1745 of Fort St David near Cuddalore.

In the course of this research I have unearthed many stories covering the lives of many of the ordinary soldiers, which I believe deserve a wider hearing.

The Dutch established the original factory at Devanampatam (Fort St David) in about 1670, and later built a fort 700 yards north of the mouth of the Gadilam River. They quitted both places in 1678. The Madras records say that their departure was partly owing to a dispute with Sivaji.

In 1680 the Dutch returned to Cuddalore and obtained from the Marathas a grant of land there and permission to erect a factory; as will be seen later, they were in possession of the Devanampatam fort and had a lease of Manjakuppam at the time that the English bought Fort St. David in 1690; in 1693.

As so often in British History, some of the earliest soldiers were recruited in Ireland.

"October Monday ye 24th1709 Captain Courtney producing a list of the soldiers, raised by him in Ireland arriv’d here in the Hallifax & came ashore the 15th Instant, y’t they are much out of all manner of Cloathing, they being in number about thirty three & y’t they are all in Generall wanting shirting, and by a list of 15 of them they want Coats, Shoes, and Stockings, does now make his application to the board requesting they may be Cloathed, Ordered that the doe deliver what coats he hath in stors, to those that want them, so farr as they goe, as likewise Shoes stockings, & white cloth enough to make y. 2 shirts a piece, & yt. an acc’t of ye same be kept apart to be deducted out of their monthly pay."

Just as in modern times, complaints of failings in the soldiers equipment were common place.

"Agreed and order’d ye bross Dougo, and Amaru Ferrara be entertained in Capt’n Hugonin Company as Topasses pay as usuall."

Topasses were "men of the hats", called as such to distinguish them from Peons who were native born Indian's and who wore turban's. Topasses were generally of Portuguese or mixed Portuguese descent at this date.

As was also the case in Britain wrecking, or the recovery of cargo from wrecked ships was seen as a perk belonging to the local rulers. Just as in Cornwall, the locals usually got their before the rulers. The East India Company attempted to write clauses into treaties which overrode this custom in neighboroughing states for East India Company vessels.

"Thursday October 27th1709 There having been a little boat belonging to a sampan bound from Cuddalore to Madrass but meeting with Contray winds were forced back again & by a squall of wind y little boat was broke away from her stern & drove ashoar a little way out of our bounds were Sirrup Sing Tuncaneers have seized her pretending (tho’ falsely) their masters have a right to all wrecks within his Government, which is contray to several Cowles & Perwanna’s granted to the Rt. Hon’ble Comp. By ye form’r and successive Kings of ye country, & of late years from Gulphus Cawne. Is therefore agreed & ordered ye Mr. Farmer do send out twelve soldiers & twenty Peons & ye the owner of the boat to go along with them, & y’t Mr Farmer do acquaint Capt’n Hugouin with our order to the end he may send out such men, as he may confide in under the command of Sergeant Brooks, to the end he may avoid any Hostility, but that they bring in the boat & w’t belongs to it.. "

Upkeep of the buildings and fort infrastructure was a constant battle. Gunpowder was key to the forts survival, I imagine that it was more regularly maintained than the other buildings.

"SatterdayOctober the 29th 1709 The Power rooms in the Fort being very much decayed, & not safe to keep a Quantity of Powder in, tis agreed to build a new Powder Room in such a place, as shall be thought most proper for it as also a new Choultry at Cuddalore which is ready to fall down so consequently very dangerous for any to be there."

It would appear that facilities for the troops were rather rudimentary. One poor man who had only just arrived in India, and who was quite probably already ill when he arrived slipped and fell into the moat. Did they have a washroom in the barracks?

Probably not.

"30th October This morning John Henry one of the new soldiers in ye Garrison was unfortunately drowned in the moat just by the Fort Gate going to wash himself.

MondayYe 14th November 1709 Inclosing in the aforesaid generall came a Commission from the Hon’ble Councill appointing y’t Lieutenant Hercules Courtney to Command a Company of Soldiers made out of Capt’n james Davies Company at ye Fort w’ch is to consist of 150 men besides new soldiers come upon the Frederick & Hallifax, Capt’n Davis, & Capt’n Courtney having divided the two companies ‘tis agreed y’t Capt’n Courtney’s Company be drawn up, & his commission read at the head thereof with ye usuall manner of delivering him ye half pike."

The offices were often as drunk and disorderly as the men, and often fell out amongst themselves.

"March 21st 1709/10 Quarrel between Capt’n Courtney and Capt’n Davis."

Just as in modern times Cuddalore is frequently swept with huge floods as the waters come down from the huge inland catchment area which stretches away over 250 miles to the west, nearly to the Ghats.

"April 3rd 1710 This day broke our a Large Barr to the Southward of the ffort occasion’d by Great Rains & Currants of Water w’ch came out of the Country. Fort St David."

The gunners were considered a cut above the rest of the ordinary soldiers, and lived apart in the gunroom. They had priviledges not granted to soldiers, such as the right to brew Toddy or Arrack for sale to the visiting sailors. Sadly however this did not always work in their favour, for when the ships were absent, which could be nine or more months away, they tended to drink themselves into oblivion. They were less likely to leave the fort on escort duty, and were more prone to commit suicide than were the soldiers.

"19th June 1710. Thomas Cassar is entertained in the Gunroom at the usual pay to serve 3 years.

Stephen Deas a Topass is entertained in Capt’n Davis’s company at the usual pay."

"20th June 1710. This morning Capt’n James Davies arrived from Madras overland & brought with him a general letter dated the 17th Instant.

21st June 1710. David Antony, Bastian Antony, Anthony Lopes, Lewis de Silva Topass are entertained in Capt’n Davis Compy at the usual pay.

Monday June 26 1710. Anthony de Rosiro is entertained in Captain Hugoens company at the usual pay."

In the unsettled conditions recruiting went on at an increased rate with many of the men being of Portuguese, or mixed Portuguese Indian race. These men were called Topasses and where valued more highly than Indian’s who were known as Peons, but less valued than northern European’s.

"Wednesday, August 2 1710.

Gaspar Roy, Joseph Row, Antony Texeira, Manuel De Costa, Dominigo de Mount, Pasqual Deas & Ventura Ferrera are entertained in Captain Hugonin’s Company at the usual pay of Topasses."

It would appear that the European's and the Topasses were paraded together in the same companies.

Conditions for the soldiers were often extremely harsh, and the distant EIC board was less than sympathetic to the conditions of their men who were often underpaid and in arrears.

The ready availability of drink did not help matters either. The right to sell or “farm” arrack to the troops was sold by “outcry” or auction every year. The farmers often gave credit to the soldiers, and then tried to claim the money back directly from the EIC at pay day. This led to many abuses.

"Monday August 21st 1710.

At a Consultation.

They allso order in said General that for the future no Retailer of Arrack do presume to trust any of the Millitary, below the degree of sergeant, on penalty of loosing their money & that no stoppage be made at the pay Table but for Diet & Ammunition Coats, which order they would have published in Cuddalore, & Tevenapatam, by beat of Tom Tom & fixing papers in Several languages at the usual places which is accordingly done & notice given that the arrack license (w’h expires the last day of this month) will be put up at Publick outcry at the fort on Monday next being the 28th Instant."

The combination of depression, homesickness and drink all to often led to men going off the rails. As is illustrated by the following deaths the following month.

3rd September 1710.

"Last night Corporal Knight run off his guard Villarenutta about one mile out of our bounds, where he killed a man & was brought in this morning after having been severely beat by the country people.

8th. This morning said Corporal died & was interred in the Evening."

Even without drink, life was often short. Between 30 and 40 men were landed as soldiers each year at Fort St. David. Within a year only about 10 would still be alive.

"17th This morning James Hearn a Centinell of this Garrison departed this life & was interred in the Evening."

These survivors were especially valued as they were considered as "seasoned" because they were seen as being more likely to survive than would new recruits. The soldiers contracts were for five years, and these seasoned men were often offered large bonuses to sign on again, rather than to return home. This was not alturism on the part of the East India Company, but hard headed business sense, because the cost and waste in new recruits was enormous. Only men at the margins of society, or refugees would sign on in Europe, as they recognised it to be a one way trip for all but a tiny lucky minority.

Even the officers were often so drunk that they could not maintain discipline.

"18th Sept 1710.

And it being ordered in said Genl; to break Ensign Carter his Commission for Sergeant Brooks to be made Ensign in his stead. Was this day read at the head of the Company & Delivered him.

Francis Sharhaler, Enoch Vouters, & Loucas Carly are entered in the Gunroom at usual pay."

Ensign Carter had been so incapacitated by drink when six of his men deserted, that he had not been able to take steps to stop them.

“They likewise advise that the orders sent them hence for reducing Military Officers pay according to what appointed by the Honbl Compas. Letter recd. Per the Susannah has caus’d a great noise and putt the Garrison upon a ferment, insomuch that on the 27th. last past a Sergeant & five Centinells deserted and run away with their arms, and a great many more designd to doe the like had they not been prevented in due time by a watchfull eye over them, They also advise that Ensign Carter was timely advis’d of their running away but being drunk took no notice of it till four hours after they were gone, and this having been his frequent practice, of which he has been often admonish’d, it’s therefore Agreed that he be broke and that a Commission be drawn out to appoint Sergt Edward Brookes (he being well recommended to us) Ensign, in his stead.”

Sergeant Brooks had previously run the armoury at Cuddalore.

"2nd October 1710. Sergeant Brooks being made an Ensign the care & charge of the armoury at Cuddalore becomes vacant thereby & Sergeant Hobey being esteemed a fitting Person to officiate in the said employ tis agreed that he should look after the same.",

Life as an East Company Soldier appears to have been fairly tough during this period.

Nick Balmer

December 2006

Sources

Madras Gazetteers South Arcot published 1906 Page 38

From British Library

IOR G/18/2/PT3,

IOR G/18/2 PT2.

IOR G/18/2 PT2.

IOR G/18/2 PT2.

IOR G/18/2 PT2.

Diary and Consultation Book 1710. Page 92.

IOR G/18/2/ PT 2.

Monday, November 13, 2006

Sunday, November 12, 2006

The Dutch Arrive at Cuddalore

Cuddalore History

Although Captain Bickley and the English East India Company had traded briefly at Tegnapatam during 1624, it does not appear that the town was particularly attractive to the English merchants. Between 1624 and 1680 it appears that trading was carried out all along this coast but that no permanent base seems to have been acquired at Cuddalore.

The nearby towns of Porto Novo and Pondicherry seem to have offered better opportunities for trade. Porto Novo is located about 18 miles south of Cuddalore, and was originally founded by the Portuguese.

Alexander Hamilton described Porto Novo, which he visited at some time after 1688 and before about 1720 as: -

“the next Place of Commerce is Porto Novo, so called by the Portugueze, when the Sea-coasts of India belonged to them; but when Aurengzeb subdued Golcondah, and the Portuguese Affairs declined, the Mogul set a Fouzdaar in it, and gave it the Name of Mahomet Bandar. The Europeans generally call it by its first Name, and the Natives by the last. The Country is fertile, healthful and pleasant, and produceth good Cotton Cloth of several Qualities and Denominations, which they sell at Home, or export to Pegu, Tanasareem, Quedah, Johore, and Atcheen on Sumatra. The Bulk of the people are Pagans.” 1

Some idea of the scale of the trade by the East India Company from Porto Novo during this period can be gained from the following account of an attack by “Xaigee” on the port, which is contained in a letter dated 19th October 1661.

“Wee are much aggrieved to heare how you are abused by the Surat Governor, and that hee hath confined you prisoners to the Companies howse. If this bee indured by these governours, they will presume further; and wee have the like complaint to present concerning Xaigee (whoe is father to him that is the Visapore generall and hath Mr. Revington in durance); for hee came here in July last [1660]to Porto Novo and robbed and pillaged the towne; whereof the Companies merchants were the greatest loosers, having taken from them in elephants, calicoes, broad cloth, copper, benjamen, etc. goodes to the value of 30,000 pardawes, and are utterly unable to pay the Company their remaynes in their handes, being about 4,000 pa[godas], unlesse our masters will license us to vindicate them by their shipping at sea, for this Xaigee hath now Porto Novo in possession. And shall expect your advice how you will direct us for the vindicating of our masters in this businesse and their merchants. These happaing but two days before the arrival of Capt. Kilvert in the Concord in that port: whome we had appointed to take in those effects, but instead of goodes brought us these sad tidings." 2

William Foster identified Xaigee (as the English wrote in 1660) as Shahaji, Shivajis father, but it would appear that Shahaji died in about 1657 while on a hunt, after falling off his horse, so this does not appear to fit, and it must be another Mahratta.

It is not clear where these goods assembled at Porto Novo came from but it is quite likely that they came from not just the town itself, but also from the villages in the hinterland, including probably Cuddalore and its surrounding villages.

The requests for permission for “vindication” in the phase “to vindicate them by their shipping at sea” might be asking for the right to carry out retaliatory raids on Indian shipping by privateering. It would appear from correspondence in the following year that much of what the Mahrattas had seized was actually not just goods belonging to the East India Company, but also private trade goods belonging to the EIC merchants themselves. No doubt this personal loss gave an added impetus to seek revenge in order to try to recoup their losses.

A small team of East India Company employees were based in Porto Novo, and these men were employing local labour to wash and pack the cargoes for onward shipping.

“one Samuell Hanmer, whome the Company hath appointed, with some other English, to goe upon the ship for Pollaroone. This Hanmer hath had employement from us in Porta Nova and Pullecherry, imbaling our goodes and looking to our washers, till the places were destroyed by the Vizapore’s army… With this same Hanmer there goeth six English [Soldiers]" 3

On the 28th of November 1660 Chamber and Shingler at Madras wrote home that there was now no reason for ships to call at Porto Novo since “the towne is wholly destroyed and all the merchants totally ruined by Xagee, the Visapore King’s generall.”

The town of Porto Novo recovered in time, but the focus of trade moved to Cuddalore over the following years.

K. Kanniah in his book Cuddalore on the Coromandel Coast under the English says that Damiao Paes, a Portuguese was appointed Captain of Cuddalore in 1584, and that he rebuilt the port with the approval of the Nayak of Gingee.

There appears to have been an Indian fort on the northern bank of the River Gadelam, which pre-dated the arrival of the European’s.

The focus of development appears to have been at Devanampattinam, which later became the site where the English eventually laid out the site of Cuddalore New Town.

The Dutch had probably visited the port before 1608, however it was in 1608 that they secured permission from the Nayak of Senji to rebuild the old Indian fort at Devanampattinam.

In 1632 on the 5th of November Emanuel Altham an EIC factor at Armagon thanked Colley for sending some goods up from the south by a boat belonging to “Mallaioes” which had arrived in great danger at Tegnapatam, having narrowly survived a great hurricane. So it would appear that the port was being used for coasting trade.

The Dutch established factories at Porto Novo and Devanampatam (Fort St David) at a later period, and built a fort at the latter some 700 yards north of the mouth of the Gadilam River. They quitted both places in 1678. The Madras records say that their departure was partly owing to a dispute with Sivaji’s men about shipping dues at Porto Novo and partly owing to a dispute because their masters at Batavia, the Dutch head-quarters, had been “abating and cutting off of their Quallety’s, sallorys and allowances.”

However this may be, one day in 1678 several of their ships appeared off the coast and the Dutch “did then immediately imbarque all their goods, lumber and weomen and send them away to Pollicat.” In 1680 they returned to Porto Novo and obtained from the Marathas a grant of land there and permission to erect a factory; as will be seen later, they were in possession of the Devanampatam fort and had a lease of Manjakuppam at the time that the English bought Fort St. David in 1690; in 1693, they took Pondicherry from the French and held it for several years afterwards; but otherwise their doings had little effect on the chronicles of the district and it will not be necessary to refer to them again.” 4

Sadly at present we have not been able to locate any extant Dutch or Portuguese records of events in Cuddalore or Porto Novo during this period.

We would be very pleased to hear from anybody who can point us in the right direction for further contemporary accounts of these ports.

1 Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies:… page 353.

2 William Foster The English Factories 1661-64 page 50.

3 Foster page 51.

4 Madras Gazetteers South Arcot published 1906 Page 38

Although Captain Bickley and the English East India Company had traded briefly at Tegnapatam during 1624, it does not appear that the town was particularly attractive to the English merchants. Between 1624 and 1680 it appears that trading was carried out all along this coast but that no permanent base seems to have been acquired at Cuddalore.

The nearby towns of Porto Novo and Pondicherry seem to have offered better opportunities for trade. Porto Novo is located about 18 miles south of Cuddalore, and was originally founded by the Portuguese.

Alexander Hamilton described Porto Novo, which he visited at some time after 1688 and before about 1720 as: -

“the next Place of Commerce is Porto Novo, so called by the Portugueze, when the Sea-coasts of India belonged to them; but when Aurengzeb subdued Golcondah, and the Portuguese Affairs declined, the Mogul set a Fouzdaar in it, and gave it the Name of Mahomet Bandar. The Europeans generally call it by its first Name, and the Natives by the last. The Country is fertile, healthful and pleasant, and produceth good Cotton Cloth of several Qualities and Denominations, which they sell at Home, or export to Pegu, Tanasareem, Quedah, Johore, and Atcheen on Sumatra. The Bulk of the people are Pagans.” 1

Some idea of the scale of the trade by the East India Company from Porto Novo during this period can be gained from the following account of an attack by “Xaigee” on the port, which is contained in a letter dated 19th October 1661.

“Wee are much aggrieved to heare how you are abused by the Surat Governor, and that hee hath confined you prisoners to the Companies howse. If this bee indured by these governours, they will presume further; and wee have the like complaint to present concerning Xaigee (whoe is father to him that is the Visapore generall and hath Mr. Revington in durance); for hee came here in July last [1660]to Porto Novo and robbed and pillaged the towne; whereof the Companies merchants were the greatest loosers, having taken from them in elephants, calicoes, broad cloth, copper, benjamen, etc. goodes to the value of 30,000 pardawes, and are utterly unable to pay the Company their remaynes in their handes, being about 4,000 pa[godas], unlesse our masters will license us to vindicate them by their shipping at sea, for this Xaigee hath now Porto Novo in possession. And shall expect your advice how you will direct us for the vindicating of our masters in this businesse and their merchants. These happaing but two days before the arrival of Capt. Kilvert in the Concord in that port: whome we had appointed to take in those effects, but instead of goodes brought us these sad tidings." 2

William Foster identified Xaigee (as the English wrote in 1660) as Shahaji, Shivajis father, but it would appear that Shahaji died in about 1657 while on a hunt, after falling off his horse, so this does not appear to fit, and it must be another Mahratta.

It is not clear where these goods assembled at Porto Novo came from but it is quite likely that they came from not just the town itself, but also from the villages in the hinterland, including probably Cuddalore and its surrounding villages.

The requests for permission for “vindication” in the phase “to vindicate them by their shipping at sea” might be asking for the right to carry out retaliatory raids on Indian shipping by privateering. It would appear from correspondence in the following year that much of what the Mahrattas had seized was actually not just goods belonging to the East India Company, but also private trade goods belonging to the EIC merchants themselves. No doubt this personal loss gave an added impetus to seek revenge in order to try to recoup their losses.

A small team of East India Company employees were based in Porto Novo, and these men were employing local labour to wash and pack the cargoes for onward shipping.

“one Samuell Hanmer, whome the Company hath appointed, with some other English, to goe upon the ship for Pollaroone. This Hanmer hath had employement from us in Porta Nova and Pullecherry, imbaling our goodes and looking to our washers, till the places were destroyed by the Vizapore’s army… With this same Hanmer there goeth six English [Soldiers]" 3

On the 28th of November 1660 Chamber and Shingler at Madras wrote home that there was now no reason for ships to call at Porto Novo since “the towne is wholly destroyed and all the merchants totally ruined by Xagee, the Visapore King’s generall.”

The town of Porto Novo recovered in time, but the focus of trade moved to Cuddalore over the following years.

K. Kanniah in his book Cuddalore on the Coromandel Coast under the English says that Damiao Paes, a Portuguese was appointed Captain of Cuddalore in 1584, and that he rebuilt the port with the approval of the Nayak of Gingee.

There appears to have been an Indian fort on the northern bank of the River Gadelam, which pre-dated the arrival of the European’s.

The focus of development appears to have been at Devanampattinam, which later became the site where the English eventually laid out the site of Cuddalore New Town.

The Dutch had probably visited the port before 1608, however it was in 1608 that they secured permission from the Nayak of Senji to rebuild the old Indian fort at Devanampattinam.

In 1632 on the 5th of November Emanuel Altham an EIC factor at Armagon thanked Colley for sending some goods up from the south by a boat belonging to “Mallaioes” which had arrived in great danger at Tegnapatam, having narrowly survived a great hurricane. So it would appear that the port was being used for coasting trade.

The Dutch established factories at Porto Novo and Devanampatam (Fort St David) at a later period, and built a fort at the latter some 700 yards north of the mouth of the Gadilam River. They quitted both places in 1678. The Madras records say that their departure was partly owing to a dispute with Sivaji’s men about shipping dues at Porto Novo and partly owing to a dispute because their masters at Batavia, the Dutch head-quarters, had been “abating and cutting off of their Quallety’s, sallorys and allowances.”

However this may be, one day in 1678 several of their ships appeared off the coast and the Dutch “did then immediately imbarque all their goods, lumber and weomen and send them away to Pollicat.” In 1680 they returned to Porto Novo and obtained from the Marathas a grant of land there and permission to erect a factory; as will be seen later, they were in possession of the Devanampatam fort and had a lease of Manjakuppam at the time that the English bought Fort St. David in 1690; in 1693, they took Pondicherry from the French and held it for several years afterwards; but otherwise their doings had little effect on the chronicles of the district and it will not be necessary to refer to them again.” 4

Sadly at present we have not been able to locate any extant Dutch or Portuguese records of events in Cuddalore or Porto Novo during this period.

We would be very pleased to hear from anybody who can point us in the right direction for further contemporary accounts of these ports.

1 Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies:… page 353.

2 William Foster The English Factories 1661-64 page 50.

3 Foster page 51.

4 Madras Gazetteers South Arcot published 1906 Page 38

Labels:

18th Century,

East India Company,

Fort St David,

History,

India,

Sepoys

Sunday, November 05, 2006

The First English Trading at Cuddalore

Cuddalore History

That there was fierce competition and rivalry between the different European nations for trade along the Coromandel Coast is clear from the following events at Karikal and Tranquebar, and that it was probably these events that caused the English to move back north up the coast to Cuddalore.

Captain Bickley arrived at Karikal on the 23rd of May 1624. On the following day he landed some Portuguese prisoners he had made at sea. The Danes from nearby Tranquebar soon learned of their arrival.

May 29. “The princypall of the Danes sent a letter unto our chief merchante, Mr. Joseph Cockram, that we were best for too departe, for there was no trade there too bee had for us, because they had formed [farmed] all the seaports of the Kinges between Nagapatam and Pullacatt for the use and benefit of the Kinge of Denmarke; therefore willed us agayne to bee gone, or else they would send us awaye in haste. Wee badd them doe theire worste, for wee would staye in spite of them all, they being three to one. And soe the partteye that brought the letter departed with his answer.”

Bickley then goes on to write that this Danish commander was probably James Mountney who had sailed in Captain Pring’s expedition in 1617.

On the first of June the Danes sent one of the three large ships they had on the coast to check them out“and demaunded of whence wee were. I bad them looke up to the flage; so presentlye hee departed, without any more wordes the one too the other.”

On the 2nd of June the Indian Governor of Karikal received a letter from the ruler of Tanjore saying that the English were welcome to trade on the coast. On the following two days the English landed two demi culverins as presents for the ruler. These were large cannon of considerable power. No doubt these cannon were a highly acceptable gift to the ruler of Tanjore, as they must have materially enhanced the power of his army.

The Danes meanwhile were taking practical steps to make things as difficult as they possible could for the English ship in order to drive it away. There was probably already trouble amongst the English crew, for on the 6th of June 1624 ten of her men deserted with the ships pinnace. This rowing and fast sailing boat was designed to be able to operate independently of the Hart, and was the type of boat that the English habitually used for scouting and raiding.

Almost immediately these deserters turned pirate and flying the English flag they took what was referred to as a junk. This ship belonged to the Governor of Negapatam and was carrying silver worth 8,000 rials of eight. They then sent a letter to Karikal inviting the other members of the crew to run away and join them. Five more English sailors ran away to join the previous deserters.

This of course left Captain Bickley short handed, and in deep trouble with the local Governors over the piracy. The Danes were not slow to exploit these difficulties. They offered the ruler of Tanjore great bribes to get him to refuse to deal with them.

By the 11th of July the English had sailed on to Tranquebar, where they landed at the fort. The Danes: -

“did couller there former malice in givinge that entertainement unto our merchants, the which they did not exspeckt at there hands; for at there coming and goeing they shott of 150 peece of ordinance from there forte and out of there three shipps. This out of there love gave us a plaster for to cure the wound they gave us at the Kings Courte.”

This demonstration of Danish potential firepower probably gave added cause for Captain Bickley to sail north to Tegnapatam. A return visit by the Danes to the ship on the 14th was cancelled. The English merchants returned to the Harte on the 15th but so many English sailors were missing ashore that they could not sail. Bickley suspected the Danes of enticing them away “by menes of James Mounttany.”

After presumably sending parties ashore to round up his sailors, the Harte finally sailed away on the morning of the 17th of July 1624. The Danes saluted her parting with at least forty guns. As this number of cannon shots was considerably more than the captain would have normally been entitled to by his status, it is likely that there was an element of derision and mockery in the Danes cannonade.

That evening they anchored off Tegnapatam “right against the Malloyes howse, the which is Governour of that towne of Tignapatann.”

On the following day, the 18th of July Mr. Cockram a merchant on the ship landed to “see the Malloyes brother” about some cloth they were to take on board their ship.

On the same day Captain Bickley wrote: -

“When you are are thwarte of the roade you shall see a great pagod, the which when yt is West and by northe from you, then it is just over the Malloyes howse… the Malloyes howse is all very white, and soe it is about the pagod, the which is too bee sene at the least four or five leages of in faire and cleare weather.”

They only stayed off Tegnapatam for one day before sailing north on the 19th of July to Poullaserre or Podasera, which is thought to be Pondicherry. It was described as being four leagues off from Tegnapatam. The town had a very white pagoda in the middle of the town.

Timber that the Harte had bought from Batavia was landed for the Malloye who appears to have controlled much of the trade along this coast, as he appears several times in the accounts of trade up and down the coast as far as Pullicatt. On the 23rd of July an official of the Ruler of Tanjore came on board the Harte and offered the merchants a house and the right to settle in Pullasera. The merchants said that they would return with an answer next year. Between the 24th and 29th of July they loaded salt into the ship as ballast, before departing on the 3rd of August for the north.

The voyage appears to have been a commercial disappointment to the East India Company merchants. The diary of John Goning at Batavia contains an entry dated 20th of November 1624. It is interesting because it shows that the English were still at that point not really interested in locally made cloth and but been hoping to tap into the pepper trade. They were hoping to find that pepper grown on the Ghats inland of the Malabar coast, which was denied to them by the dominant Portuguese and Dutch who controlled the Malabar ports like Kochi and Calicut.

“The ship Hart arrived heer from the Coast of Coromandel. In her returned Mr. Joseph Cockram and Mr. Georg Bruen, with others sent to settle a factory in the Nayck of Tanjours country, having effected nothing ther, more than the buying in of 19 or 20 bales of cloth; finding the country to yeeld but little pepper of a very small sort and that allwayes much wett with the fresh water in portage from the upland mountains. Allso they found the Naick or King very covertous, expecting very great presents yearly, besides payment of 7,000 rials of eight every yeer for use and custome of his porte Cercall, which he would apoynt for us. Howbeit, they found the porte Poodysera, in another Naiks country nearer adjoining to St. Tome, to be a fitter place to procure all sorts of clothing, therabout or about Petepoly made, then in the said Nayck of Tanjours land; and from Naick of Poodysera they had a writing giving the English leave the next yeer to come and settle ther, paying only the custom of 2 ½ per cento, or renting the porte, as wee can best agree.”

That there was fierce competition and rivalry between the different European nations for trade along the Coromandel Coast is clear from the following events at Karikal and Tranquebar, and that it was probably these events that caused the English to move back north up the coast to Cuddalore.

Captain Bickley arrived at Karikal on the 23rd of May 1624. On the following day he landed some Portuguese prisoners he had made at sea. The Danes from nearby Tranquebar soon learned of their arrival.

May 29. “The princypall of the Danes sent a letter unto our chief merchante, Mr. Joseph Cockram, that we were best for too departe, for there was no trade there too bee had for us, because they had formed [farmed] all the seaports of the Kinges between Nagapatam and Pullacatt for the use and benefit of the Kinge of Denmarke; therefore willed us agayne to bee gone, or else they would send us awaye in haste. Wee badd them doe theire worste, for wee would staye in spite of them all, they being three to one. And soe the partteye that brought the letter departed with his answer.”

Bickley then goes on to write that this Danish commander was probably James Mountney who had sailed in Captain Pring’s expedition in 1617.

On the first of June the Danes sent one of the three large ships they had on the coast to check them out“and demaunded of whence wee were. I bad them looke up to the flage; so presentlye hee departed, without any more wordes the one too the other.”

On the 2nd of June the Indian Governor of Karikal received a letter from the ruler of Tanjore saying that the English were welcome to trade on the coast. On the following two days the English landed two demi culverins as presents for the ruler. These were large cannon of considerable power. No doubt these cannon were a highly acceptable gift to the ruler of Tanjore, as they must have materially enhanced the power of his army.

The Danes meanwhile were taking practical steps to make things as difficult as they possible could for the English ship in order to drive it away. There was probably already trouble amongst the English crew, for on the 6th of June 1624 ten of her men deserted with the ships pinnace. This rowing and fast sailing boat was designed to be able to operate independently of the Hart, and was the type of boat that the English habitually used for scouting and raiding.

Almost immediately these deserters turned pirate and flying the English flag they took what was referred to as a junk. This ship belonged to the Governor of Negapatam and was carrying silver worth 8,000 rials of eight. They then sent a letter to Karikal inviting the other members of the crew to run away and join them. Five more English sailors ran away to join the previous deserters.

This of course left Captain Bickley short handed, and in deep trouble with the local Governors over the piracy. The Danes were not slow to exploit these difficulties. They offered the ruler of Tanjore great bribes to get him to refuse to deal with them.

By the 11th of July the English had sailed on to Tranquebar, where they landed at the fort. The Danes: -

“did couller there former malice in givinge that entertainement unto our merchants, the which they did not exspeckt at there hands; for at there coming and goeing they shott of 150 peece of ordinance from there forte and out of there three shipps. This out of there love gave us a plaster for to cure the wound they gave us at the Kings Courte.”

This demonstration of Danish potential firepower probably gave added cause for Captain Bickley to sail north to Tegnapatam. A return visit by the Danes to the ship on the 14th was cancelled. The English merchants returned to the Harte on the 15th but so many English sailors were missing ashore that they could not sail. Bickley suspected the Danes of enticing them away “by menes of James Mounttany.”

After presumably sending parties ashore to round up his sailors, the Harte finally sailed away on the morning of the 17th of July 1624. The Danes saluted her parting with at least forty guns. As this number of cannon shots was considerably more than the captain would have normally been entitled to by his status, it is likely that there was an element of derision and mockery in the Danes cannonade.

That evening they anchored off Tegnapatam “right against the Malloyes howse, the which is Governour of that towne of Tignapatann.”

On the following day, the 18th of July Mr. Cockram a merchant on the ship landed to “see the Malloyes brother” about some cloth they were to take on board their ship.

On the same day Captain Bickley wrote: -

“When you are are thwarte of the roade you shall see a great pagod, the which when yt is West and by northe from you, then it is just over the Malloyes howse… the Malloyes howse is all very white, and soe it is about the pagod, the which is too bee sene at the least four or five leages of in faire and cleare weather.”

They only stayed off Tegnapatam for one day before sailing north on the 19th of July to Poullaserre or Podasera, which is thought to be Pondicherry. It was described as being four leagues off from Tegnapatam. The town had a very white pagoda in the middle of the town.

Timber that the Harte had bought from Batavia was landed for the Malloye who appears to have controlled much of the trade along this coast, as he appears several times in the accounts of trade up and down the coast as far as Pullicatt. On the 23rd of July an official of the Ruler of Tanjore came on board the Harte and offered the merchants a house and the right to settle in Pullasera. The merchants said that they would return with an answer next year. Between the 24th and 29th of July they loaded salt into the ship as ballast, before departing on the 3rd of August for the north.

The voyage appears to have been a commercial disappointment to the East India Company merchants. The diary of John Goning at Batavia contains an entry dated 20th of November 1624. It is interesting because it shows that the English were still at that point not really interested in locally made cloth and but been hoping to tap into the pepper trade. They were hoping to find that pepper grown on the Ghats inland of the Malabar coast, which was denied to them by the dominant Portuguese and Dutch who controlled the Malabar ports like Kochi and Calicut.

“The ship Hart arrived heer from the Coast of Coromandel. In her returned Mr. Joseph Cockram and Mr. Georg Bruen, with others sent to settle a factory in the Nayck of Tanjours country, having effected nothing ther, more than the buying in of 19 or 20 bales of cloth; finding the country to yeeld but little pepper of a very small sort and that allwayes much wett with the fresh water in portage from the upland mountains. Allso they found the Naick or King very covertous, expecting very great presents yearly, besides payment of 7,000 rials of eight every yeer for use and custome of his porte Cercall, which he would apoynt for us. Howbeit, they found the porte Poodysera, in another Naiks country nearer adjoining to St. Tome, to be a fitter place to procure all sorts of clothing, therabout or about Petepoly made, then in the said Nayck of Tanjours land; and from Naick of Poodysera they had a writing giving the English leave the next yeer to come and settle ther, paying only the custom of 2 ½ per cento, or renting the porte, as wee can best agree.”

Labels:

East India Company,

Fort St David,

History,

India

The First English arrive at Cuddalore

Cuddalore History

The earliest record of an English ship visiting Cuddalore that I can find occurred on the May 21st 1624 when Captain John Bickley made his land fall at Tegnapatam, whilst sailing in his ship the Hart from Batavia to India as he recorded: -

“Tignapatam hath over yt a greate pagod and a whyte howse which is sene some three leagues of. 1”

Tegnapatam was the name by which the Dutch and early English voyagers called Cuddalore. Captain Bickley goes on to describe the coast.

“To the southerd of Tegnapatam some three leages there is four pagodas, as it were four great trees… This four pagodas is a towne so called by the names of Quarter" (2) Pagodas. Allsoe four leages too the southward of the four pagodas is a towne called Portanovy (3) , and three leges too the southward of Porttanovy is a town called Tremeldanes (4). …And three leages to the southward of Tremeldanes is the towne of the Danes, where they have there forte, called Trenkcombar(5). And some two leagues and a half too the southward of this forte is the porte of Carracall (6)."

The earliest English voyages to Asia were made to buy spices. Captain Bickley was returning from Batavia where he had been trying unsuccessfully to load pepper, due to opposition and intervention by the hostile Dutch employees of the VOC.

The London grocers and leaders of the Levant Company aimed through despatching ships to Asia to compete with the Portuguese in the spice trade when they established the East India Company in 1600.

When James Lancaster on his first expedition in 1591, entered into the Indian Ocean, he sailed directly into the Bay of Bengal on his voyage towards Malacca and the Spice Islands bypassing India entirely.

During this voyage and the other subsequent voyages between 1600 and 1608, the aim of the Company Directors was to reach the Spice Islands and not India.

It was only when it was discovered that the Spice Islanders did not wish to buy the unsuitable goods the European ships carried, and that they would only accept silver coinage in exchange for spices, that the English began to cast around for alternative ways of financing their trade.

By the third voyage to Asia profits had reached 234 per cent, however the English Government was becoming increasingly unhappy about the amount of silver coinage that was leaving England for the east. Silver in England was in short supply, and in any case originated from the Spanish American Empire.

The English had had to resort to robbery from local shipping to balance their trade, on the earlier voyages by removing goods from local vessels arriving from India, and selling them as their own.

Through this plundering the East India Company [EIC] had become aware of the considerable amount of trade occurring between India and the Spice Islands. Their ships had already seized Indian vessels travelling to Java, Malacca and Bantam, and had observed that the Indian merchants were able to exchange Coromandel textiles with the islanders for spices.

Like the earlier Portuguese traders, the English and the Dutch who faced similar problems, tried to break into this existing Asian trade between India and the Spice Islands.

So although the first trading English posts in India were set up on the west coast of India where they could break into the existing trade routes between Persia and India, the East India Company soon realised that it had to have its own trading posts on the Coromandel Coast, in order to purchase the cotton required by the islanders.

For whilst Gujarat produced the highest quality silk and cotton textiles, what was required for the trade to the Spice Islands was not silk but the cheaper cottons of the Coromandel, which sold so well to the Spice Islanders.

Although the first English voyage to India in 1591 had pre-dated the first Dutch voyage made in 1595, the Dutch with their greater expertise in running merchant shipping very quickly followed in the footsteps of the English.

With a stronger capital market in Amsterdam, the Dutch East India Company [VOC] was better able to finance its voyages than the East India Company was. The VOC soon had a market capitalisation nearly ten times as great as that of the EIC.

Dutch ships of the period were also technically superior to English ships for bulk cargo carrying, and needed smaller crews than did the equivalent English ships. As had previously occurred along the Atlantic coasts of Europe, the Dutch had rapidly become the cargo carriers of choice for the Atlantic and Baltic bulk trades.

During the same period other European nations including the Danes had quickly followed reaching the east coast of India by 1619, establishing a post at Tranquebar. Many of the employees of the Danish Asiatisk Kompagni were in fact Dutch sailors and merchants who were excluded from the Dutch East India Company, or who were former employees of the VOC.

Due to the monsoons the textile trade was seasonal for the European’s. The ships leaving the Bay of Bengal preferred to load during January each year. The local textile producers found it difficult at first to keep up with the increase in demand, and were also used to producing textiles annually to suit the domestic market, which had its peak period, during the marriage season.

At first the European ships felt their way along the coast calling at anchorages and coastal villages. Contacts were made with local Indian merchants who were already in the habit of trading with Indian and South East Asia shippers and merchants.

Very quickly it was found that it was more efficient and cost effective to establish agents or factors on shore, ready for the arrival of ships, rather than having ships wait off shore for months whilst cargoes were assembled. The factors would collect pepper or textiles throughout the year, overseeing their washing, packing and baling and storage in warehouses called godowns, until such time as they could be loaded into the ships.

These anchorages and factories were necessarily located at the major river estuaries along the coast such as the Kaveri, or Godavari.

The Dutch, Danes and English were entering into waters already full of active Indian and South East Asian merchants. Security was also a major concern, so that the sites occupied where often island sites at some little distance from the major existing Indian towns.

Local merchants strongly resisted the granting of trading rights to the northern European’s in these centres of existing trade, because they were well aware of the dangers of letting the Europeans establish themselves, following their previous experience at the hands of the Portuguese.

The first English factory was at Armagon in the Bay of Bengal, a town just north of the Pulicat lagoon.

“when in 1626 the English settled at Armagon (Durgarajupatnam ) they obtained from the local Nayak the right to coin pagodas and fanams.”

Shortly afterwards a second factory was established by the English at Masulipatam [nowadays Machilipatam] in the delta of the Godavari River in 1628.

By 1624 the situation for the English on the west coast had become very difficult, as their major trading factory was located at Surat, which was the major Mogul trading port. The Mogul traders and officials were becoming very hostile.

English ships had been seizing and plundering Mogul, Arab and Turkish vessels. The local merchants were understandably up in arms about their losses.

In 1624 due to these disputes the East India Company factors at Surat were locked up in prison, whilst huge fines were levied to compensate the aggrieved parties. It was very unclear if the EIC could continue to trade in the Mogul Empire.

This empire spread across the northern plains of India from Lahore and Surat to the mouth of the Ganges. However to the south a number of independent and semi independent Sultanates and states existed. These offered alternative routes to trade with the Indian subcontinent, even if the north was to be denied to the English.

So with Surat and quite possibly the other Mogul ports closed to them it was decided to try the Tanjore kingdom’s ports. Earlier voyages had been made to Masulipatam and also Pulicat, so that the Coromandel Coast was not entirely unknown to the English.

Mr Johnson the Factor hoped to find sufficient pepper in Tanjore to laden the Hart in three months at 18 rials per bahar of about 330 lb.

The Hart had left Batavia on the 27th of March 1624, and had narrowly survived a hurricane on the 28th of April. On the 9th of May they crossed the Line .

“May 21 Tignapatam hath over yt a greate pagod (10) and a whyte howse which is sene some three leagues of.”

The captain went on to describe the coast.

“To the southerd of Tegnapatam some three leages there is four pagodas, as it were four great trees… This four pagodas is a towne so called by the names of Quarter Pagodas. Allsoe four leages too the southward of the four pagodas is a towne called Portanovy."

These four great pagodas are thought to include the one at Tirupapuliyur, and those at Chidambaram.

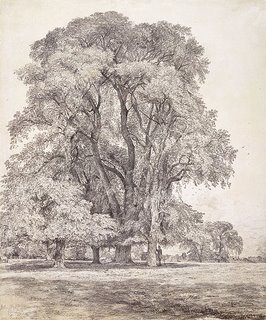

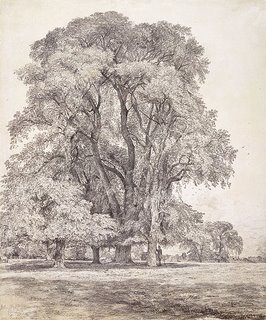

That these great pagodas should look like trees to the English sailors “four pagodas, as it were four great trees” is not surprising if you compare their profile with the following drawing of an Elm Tree by John Constable . These great dark trees, which towered over the English countryside, must have looked much like Chidambaram pagoda.

11.

12.

The Hart did not land at Tegnapatam at this first visit, but sailed towards the south to anchor at Karikal on May the 23rd.

On May 24th the captain and the merchants went ashore and where kindly entertained by the Governor

“wee being the first English ship that had ever bin in theis partes before.”

The Indian governor at Karikal was friendly, and promised to advise the King at “Tangeur” [Tanjore] of their arrival.

1.The English Factories in India, 1624-1629 by William Foster published 1909. Pages 13 & 14.

2.This is probably from the Portuguese quarto meaning four. The reference is probably to the four gopuras of the great temple at Chilambaram, which are visible from a considerable distance out to sea.

3.Porto Novo

4.Discussed in Foster, thought to be Tirumullavasal which appears on Linschten’s and Hondius’s maps as Tremalavas.

5.Tranquebar.

6.Karikal.

7.58’ 48.16”N, 09’ 21.59”E

8.Notes from The English Factories in India 1655-60, by William Forster Page 34,

9.The Equator.

10.The temple at Tirupapuliyur.

11.Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia.

12. Photo from http://www.jorgetutor.com/india/sindia/chidambaram/chidambaram12.htm

The earliest record of an English ship visiting Cuddalore that I can find occurred on the May 21st 1624 when Captain John Bickley made his land fall at Tegnapatam, whilst sailing in his ship the Hart from Batavia to India as he recorded: -

“Tignapatam hath over yt a greate pagod and a whyte howse which is sene some three leagues of. 1”

Tegnapatam was the name by which the Dutch and early English voyagers called Cuddalore. Captain Bickley goes on to describe the coast.

“To the southerd of Tegnapatam some three leages there is four pagodas, as it were four great trees… This four pagodas is a towne so called by the names of Quarter" (2) Pagodas. Allsoe four leages too the southward of the four pagodas is a towne called Portanovy (3) , and three leges too the southward of Porttanovy is a town called Tremeldanes (4). …And three leages to the southward of Tremeldanes is the towne of the Danes, where they have there forte, called Trenkcombar(5). And some two leagues and a half too the southward of this forte is the porte of Carracall (6)."

The earliest English voyages to Asia were made to buy spices. Captain Bickley was returning from Batavia where he had been trying unsuccessfully to load pepper, due to opposition and intervention by the hostile Dutch employees of the VOC.

The London grocers and leaders of the Levant Company aimed through despatching ships to Asia to compete with the Portuguese in the spice trade when they established the East India Company in 1600.

When James Lancaster on his first expedition in 1591, entered into the Indian Ocean, he sailed directly into the Bay of Bengal on his voyage towards Malacca and the Spice Islands bypassing India entirely.

During this voyage and the other subsequent voyages between 1600 and 1608, the aim of the Company Directors was to reach the Spice Islands and not India.

It was only when it was discovered that the Spice Islanders did not wish to buy the unsuitable goods the European ships carried, and that they would only accept silver coinage in exchange for spices, that the English began to cast around for alternative ways of financing their trade.

By the third voyage to Asia profits had reached 234 per cent, however the English Government was becoming increasingly unhappy about the amount of silver coinage that was leaving England for the east. Silver in England was in short supply, and in any case originated from the Spanish American Empire.

The English had had to resort to robbery from local shipping to balance their trade, on the earlier voyages by removing goods from local vessels arriving from India, and selling them as their own.

Through this plundering the East India Company [EIC] had become aware of the considerable amount of trade occurring between India and the Spice Islands. Their ships had already seized Indian vessels travelling to Java, Malacca and Bantam, and had observed that the Indian merchants were able to exchange Coromandel textiles with the islanders for spices.

Like the earlier Portuguese traders, the English and the Dutch who faced similar problems, tried to break into this existing Asian trade between India and the Spice Islands.

So although the first trading English posts in India were set up on the west coast of India where they could break into the existing trade routes between Persia and India, the East India Company soon realised that it had to have its own trading posts on the Coromandel Coast, in order to purchase the cotton required by the islanders.

For whilst Gujarat produced the highest quality silk and cotton textiles, what was required for the trade to the Spice Islands was not silk but the cheaper cottons of the Coromandel, which sold so well to the Spice Islanders.

Although the first English voyage to India in 1591 had pre-dated the first Dutch voyage made in 1595, the Dutch with their greater expertise in running merchant shipping very quickly followed in the footsteps of the English.

With a stronger capital market in Amsterdam, the Dutch East India Company [VOC] was better able to finance its voyages than the East India Company was. The VOC soon had a market capitalisation nearly ten times as great as that of the EIC.

Dutch ships of the period were also technically superior to English ships for bulk cargo carrying, and needed smaller crews than did the equivalent English ships. As had previously occurred along the Atlantic coasts of Europe, the Dutch had rapidly become the cargo carriers of choice for the Atlantic and Baltic bulk trades.

During the same period other European nations including the Danes had quickly followed reaching the east coast of India by 1619, establishing a post at Tranquebar. Many of the employees of the Danish Asiatisk Kompagni were in fact Dutch sailors and merchants who were excluded from the Dutch East India Company, or who were former employees of the VOC.

Due to the monsoons the textile trade was seasonal for the European’s. The ships leaving the Bay of Bengal preferred to load during January each year. The local textile producers found it difficult at first to keep up with the increase in demand, and were also used to producing textiles annually to suit the domestic market, which had its peak period, during the marriage season.

At first the European ships felt their way along the coast calling at anchorages and coastal villages. Contacts were made with local Indian merchants who were already in the habit of trading with Indian and South East Asia shippers and merchants.

Very quickly it was found that it was more efficient and cost effective to establish agents or factors on shore, ready for the arrival of ships, rather than having ships wait off shore for months whilst cargoes were assembled. The factors would collect pepper or textiles throughout the year, overseeing their washing, packing and baling and storage in warehouses called godowns, until such time as they could be loaded into the ships.

These anchorages and factories were necessarily located at the major river estuaries along the coast such as the Kaveri, or Godavari.

The Dutch, Danes and English were entering into waters already full of active Indian and South East Asian merchants. Security was also a major concern, so that the sites occupied where often island sites at some little distance from the major existing Indian towns.

Local merchants strongly resisted the granting of trading rights to the northern European’s in these centres of existing trade, because they were well aware of the dangers of letting the Europeans establish themselves, following their previous experience at the hands of the Portuguese.

The first English factory was at Armagon in the Bay of Bengal, a town just north of the Pulicat lagoon.

“when in 1626 the English settled at Armagon (Durgarajupatnam ) they obtained from the local Nayak the right to coin pagodas and fanams.”

Shortly afterwards a second factory was established by the English at Masulipatam [nowadays Machilipatam] in the delta of the Godavari River in 1628.

By 1624 the situation for the English on the west coast had become very difficult, as their major trading factory was located at Surat, which was the major Mogul trading port. The Mogul traders and officials were becoming very hostile.

English ships had been seizing and plundering Mogul, Arab and Turkish vessels. The local merchants were understandably up in arms about their losses.

In 1624 due to these disputes the East India Company factors at Surat were locked up in prison, whilst huge fines were levied to compensate the aggrieved parties. It was very unclear if the EIC could continue to trade in the Mogul Empire.

This empire spread across the northern plains of India from Lahore and Surat to the mouth of the Ganges. However to the south a number of independent and semi independent Sultanates and states existed. These offered alternative routes to trade with the Indian subcontinent, even if the north was to be denied to the English.

So with Surat and quite possibly the other Mogul ports closed to them it was decided to try the Tanjore kingdom’s ports. Earlier voyages had been made to Masulipatam and also Pulicat, so that the Coromandel Coast was not entirely unknown to the English.

Mr Johnson the Factor hoped to find sufficient pepper in Tanjore to laden the Hart in three months at 18 rials per bahar of about 330 lb.

The Hart had left Batavia on the 27th of March 1624, and had narrowly survived a hurricane on the 28th of April. On the 9th of May they crossed the Line .

“May 21 Tignapatam hath over yt a greate pagod (10) and a whyte howse which is sene some three leagues of.”

The captain went on to describe the coast.

“To the southerd of Tegnapatam some three leages there is four pagodas, as it were four great trees… This four pagodas is a towne so called by the names of Quarter Pagodas. Allsoe four leages too the southward of the four pagodas is a towne called Portanovy."

These four great pagodas are thought to include the one at Tirupapuliyur, and those at Chidambaram.

That these great pagodas should look like trees to the English sailors “four pagodas, as it were four great trees” is not surprising if you compare their profile with the following drawing of an Elm Tree by John Constable . These great dark trees, which towered over the English countryside, must have looked much like Chidambaram pagoda.

11.

12.

The Hart did not land at Tegnapatam at this first visit, but sailed towards the south to anchor at Karikal on May the 23rd.

On May 24th the captain and the merchants went ashore and where kindly entertained by the Governor

“wee being the first English ship that had ever bin in theis partes before.”

The Indian governor at Karikal was friendly, and promised to advise the King at “Tangeur” [Tanjore] of their arrival.

1.The English Factories in India, 1624-1629 by William Foster published 1909. Pages 13 & 14.

2.This is probably from the Portuguese quarto meaning four. The reference is probably to the four gopuras of the great temple at Chilambaram, which are visible from a considerable distance out to sea.

3.Porto Novo

4.Discussed in Foster, thought to be Tirumullavasal which appears on Linschten’s and Hondius’s maps as Tremalavas.

5.Tranquebar.

6.Karikal.

7.58’ 48.16”N, 09’ 21.59”E

8.Notes from The English Factories in India 1655-60, by William Forster Page 34,

9.The Equator.

10.The temple at Tirupapuliyur.

11.Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia.

12. Photo from http://www.jorgetutor.com/india/sindia/chidambaram/chidambaram12.htm

Labels:

18th Century,

East India Company,

Fort St David,

History,

India

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)