The earliest record of an English ship visiting Cuddalore that I can find occurred on the May 21st 1624 when Captain John Bickley made his land fall at Tegnapatam, whilst sailing in his ship the Hart from Batavia to India as he recorded: -

“Tignapatam hath over yt a greate pagod and a whyte howse which is sene some three leagues of. 1”

Tegnapatam was the name by which the Dutch and early English voyagers called Cuddalore. Captain Bickley goes on to describe the coast.

“To the southerd of Tegnapatam some three leages there is four pagodas, as it were four great trees… This four pagodas is a towne so called by the names of Quarter" (2) Pagodas. Allsoe four leages too the southward of the four pagodas is a towne called Portanovy (3) , and three leges too the southward of Porttanovy is a town called Tremeldanes (4). …And three leages to the southward of Tremeldanes is the towne of the Danes, where they have there forte, called Trenkcombar(5). And some two leagues and a half too the southward of this forte is the porte of Carracall (6)."

The earliest English voyages to Asia were made to buy spices. Captain Bickley was returning from Batavia where he had been trying unsuccessfully to load pepper, due to opposition and intervention by the hostile Dutch employees of the VOC.

The London grocers and leaders of the Levant Company aimed through despatching ships to Asia to compete with the Portuguese in the spice trade when they established the East India Company in 1600.

When James Lancaster on his first expedition in 1591, entered into the Indian Ocean, he sailed directly into the Bay of Bengal on his voyage towards Malacca and the Spice Islands bypassing India entirely.

During this voyage and the other subsequent voyages between 1600 and 1608, the aim of the Company Directors was to reach the Spice Islands and not India.

It was only when it was discovered that the Spice Islanders did not wish to buy the unsuitable goods the European ships carried, and that they would only accept silver coinage in exchange for spices, that the English began to cast around for alternative ways of financing their trade.

By the third voyage to Asia profits had reached 234 per cent, however the English Government was becoming increasingly unhappy about the amount of silver coinage that was leaving England for the east. Silver in England was in short supply, and in any case originated from the Spanish American Empire.

The English had had to resort to robbery from local shipping to balance their trade, on the earlier voyages by removing goods from local vessels arriving from India, and selling them as their own.

Through this plundering the East India Company [EIC] had become aware of the considerable amount of trade occurring between India and the Spice Islands. Their ships had already seized Indian vessels travelling to Java, Malacca and Bantam, and had observed that the Indian merchants were able to exchange Coromandel textiles with the islanders for spices.

Like the earlier Portuguese traders, the English and the Dutch who faced similar problems, tried to break into this existing Asian trade between India and the Spice Islands.

So although the first trading English posts in India were set up on the west coast of India where they could break into the existing trade routes between Persia and India, the East India Company soon realised that it had to have its own trading posts on the Coromandel Coast, in order to purchase the cotton required by the islanders.

For whilst Gujarat produced the highest quality silk and cotton textiles, what was required for the trade to the Spice Islands was not silk but the cheaper cottons of the Coromandel, which sold so well to the Spice Islanders.

Although the first English voyage to India in 1591 had pre-dated the first Dutch voyage made in 1595, the Dutch with their greater expertise in running merchant shipping very quickly followed in the footsteps of the English.

With a stronger capital market in Amsterdam, the Dutch East India Company [VOC] was better able to finance its voyages than the East India Company was. The VOC soon had a market capitalisation nearly ten times as great as that of the EIC.

Dutch ships of the period were also technically superior to English ships for bulk cargo carrying, and needed smaller crews than did the equivalent English ships. As had previously occurred along the Atlantic coasts of Europe, the Dutch had rapidly become the cargo carriers of choice for the Atlantic and Baltic bulk trades.

During the same period other European nations including the Danes had quickly followed reaching the east coast of India by 1619, establishing a post at Tranquebar. Many of the employees of the Danish Asiatisk Kompagni were in fact Dutch sailors and merchants who were excluded from the Dutch East India Company, or who were former employees of the VOC.

Due to the monsoons the textile trade was seasonal for the European’s. The ships leaving the Bay of Bengal preferred to load during January each year. The local textile producers found it difficult at first to keep up with the increase in demand, and were also used to producing textiles annually to suit the domestic market, which had its peak period, during the marriage season.

At first the European ships felt their way along the coast calling at anchorages and coastal villages. Contacts were made with local Indian merchants who were already in the habit of trading with Indian and South East Asia shippers and merchants.

Very quickly it was found that it was more efficient and cost effective to establish agents or factors on shore, ready for the arrival of ships, rather than having ships wait off shore for months whilst cargoes were assembled. The factors would collect pepper or textiles throughout the year, overseeing their washing, packing and baling and storage in warehouses called godowns, until such time as they could be loaded into the ships.

These anchorages and factories were necessarily located at the major river estuaries along the coast such as the Kaveri, or Godavari.

The Dutch, Danes and English were entering into waters already full of active Indian and South East Asian merchants. Security was also a major concern, so that the sites occupied where often island sites at some little distance from the major existing Indian towns.

Local merchants strongly resisted the granting of trading rights to the northern European’s in these centres of existing trade, because they were well aware of the dangers of letting the Europeans establish themselves, following their previous experience at the hands of the Portuguese.

The first English factory was at Armagon in the Bay of Bengal, a town just north of the Pulicat lagoon.

“when in 1626 the English settled at Armagon (Durgarajupatnam ) they obtained from the local Nayak the right to coin pagodas and fanams.”

Shortly afterwards a second factory was established by the English at Masulipatam [nowadays Machilipatam] in the delta of the Godavari River in 1628.

By 1624 the situation for the English on the west coast had become very difficult, as their major trading factory was located at Surat, which was the major Mogul trading port. The Mogul traders and officials were becoming very hostile.

English ships had been seizing and plundering Mogul, Arab and Turkish vessels. The local merchants were understandably up in arms about their losses.

In 1624 due to these disputes the East India Company factors at Surat were locked up in prison, whilst huge fines were levied to compensate the aggrieved parties. It was very unclear if the EIC could continue to trade in the Mogul Empire.

This empire spread across the northern plains of India from Lahore and Surat to the mouth of the Ganges. However to the south a number of independent and semi independent Sultanates and states existed. These offered alternative routes to trade with the Indian subcontinent, even if the north was to be denied to the English.

So with Surat and quite possibly the other Mogul ports closed to them it was decided to try the Tanjore kingdom’s ports. Earlier voyages had been made to Masulipatam and also Pulicat, so that the Coromandel Coast was not entirely unknown to the English.

Mr Johnson the Factor hoped to find sufficient pepper in Tanjore to laden the Hart in three months at 18 rials per bahar of about 330 lb.

The Hart had left Batavia on the 27th of March 1624, and had narrowly survived a hurricane on the 28th of April. On the 9th of May they crossed the Line .

“May 21 Tignapatam hath over yt a greate pagod (10) and a whyte howse which is sene some three leagues of.”

The captain went on to describe the coast.

“To the southerd of Tegnapatam some three leages there is four pagodas, as it were four great trees… This four pagodas is a towne so called by the names of Quarter Pagodas. Allsoe four leages too the southward of the four pagodas is a towne called Portanovy."

These four great pagodas are thought to include the one at Tirupapuliyur, and those at Chidambaram.

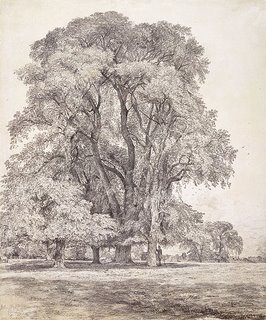

That these great pagodas should look like trees to the English sailors “four pagodas, as it were four great trees” is not surprising if you compare their profile with the following drawing of an Elm Tree by John Constable . These great dark trees, which towered over the English countryside, must have looked much like Chidambaram pagoda.

11.

12.

The Hart did not land at Tegnapatam at this first visit, but sailed towards the south to anchor at Karikal on May the 23rd.

On May 24th the captain and the merchants went ashore and where kindly entertained by the Governor

“wee being the first English ship that had ever bin in theis partes before.”

The Indian governor at Karikal was friendly, and promised to advise the King at “Tangeur” [Tanjore] of their arrival.

1.The English Factories in India, 1624-1629 by William Foster published 1909. Pages 13 & 14.

2.This is probably from the Portuguese quarto meaning four. The reference is probably to the four gopuras of the great temple at Chilambaram, which are visible from a considerable distance out to sea.

3.Porto Novo

4.Discussed in Foster, thought to be Tirumullavasal which appears on Linschten’s and Hondius’s maps as Tremalavas.

5.Tranquebar.

6.Karikal.

7.58’ 48.16”N, 09’ 21.59”E

8.Notes from The English Factories in India 1655-60, by William Forster Page 34,

9.The Equator.

10.The temple at Tirupapuliyur.

11.Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia.

12. Photo from http://www.jorgetutor.com/india/sindia/chidambaram/chidambaram12.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment